In the Line of Fire: Photojournalists discuss photographing war

By Cliff Fernandes

Cool evening winds hit the walls of a bungalow classroom where eager guests attended the war photojournalist panel “In The Line of Fire” on Oct. 19.

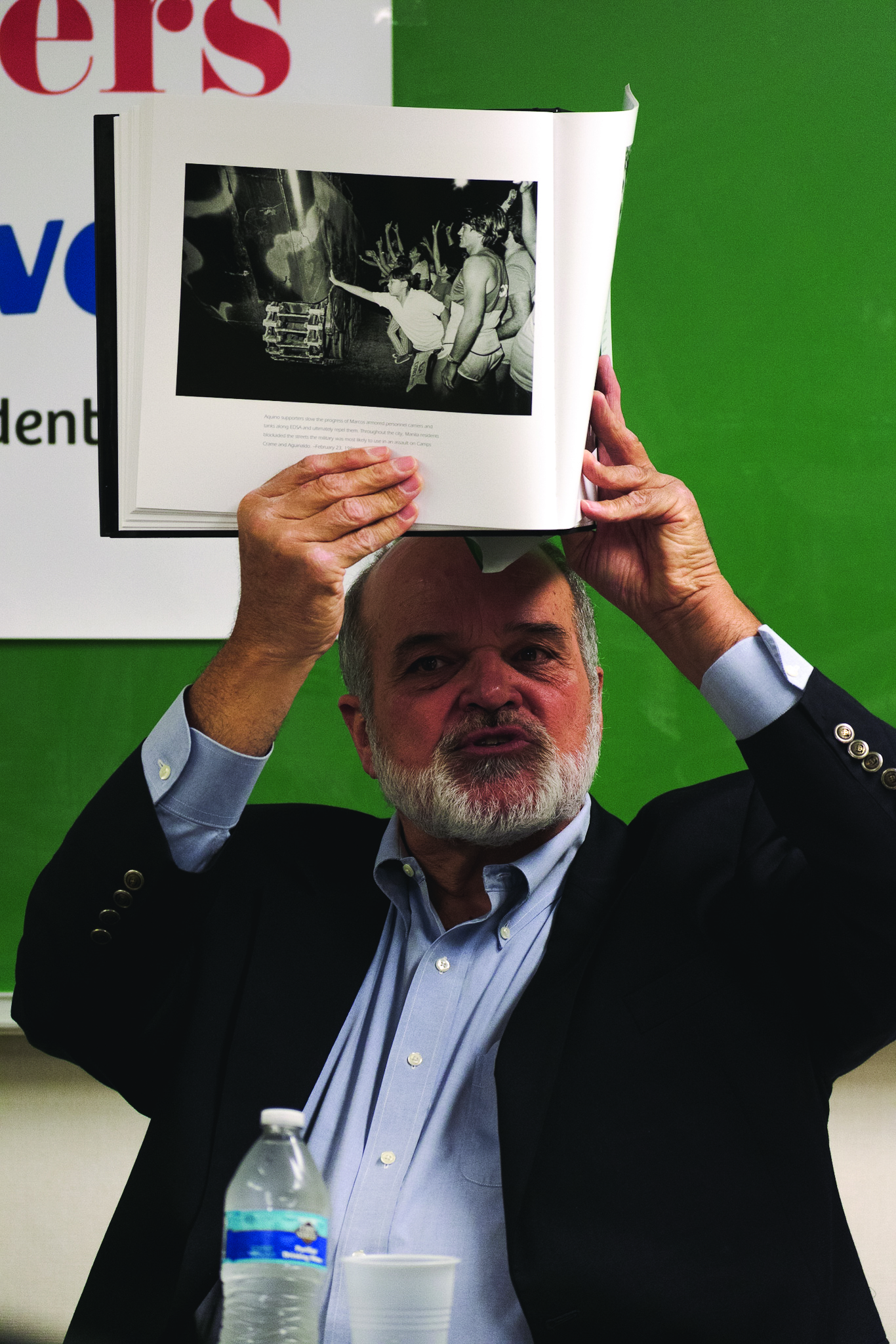

As a part of City College’s Journalism Matters month, weathered photojournalists Kim Komenich and Lou Dematteis sat at the head of the room behind a stack of thick photo-story books showcasing their coverage of mid-’90s war zones. Moderated by war journalist and author Mary Jo McConahay, the two guest speakers discussed why they believed journalism matters, now more than ever.

Photojournalism is about putting a face on the events happening around the world, Komenich said. It’s about taking the conflicts happening overseas that get broadcasted on TV, and introducing the human element.

Be it domestically or internationally, Dematteis said that an ethical press covers a story to document the truth. The objectivity journalists strive for should not be about presenting two opposing arguments — it means finding the truth, he said. For him, that meant exposing the U.S. government’s claim that Nicaragua was a threat during the Reagan Era.

“It was the poorest country I had ever been in, and [it was] a ridiculous claim that this country could somehow militarily threaten the United States, so as soon as I got there, I knew the story that should be told is not being told,” Dematteis said.

Dematteis spent six years in Nicaragua during the height of the U.S.-backed Contra War. In 1986, his photographs of U.S. mercenary Eugene Hasenfus being captured received international recognition and inclusion in The New York Times’ and National Press Photographers Association’s Pictures of the Year.

The Journalist’s Role

As technology and social media bring images worldwide into the spotlight almost instantly, it is more important now than before for journalists to understand what makes them different from most people who snap photos with their phones, Komenich said.

“We’re not just out there to do the write up of the day. We’re out there to cover people’s lives and what it’s like growing up in poverty,” Komenich said.

He raised above his head a black-and-white image of a woman and a girl next to some tombstones.

“This was a family that lives in the cemetery in Manilla, right next to the Wall Street of Philippines,” he said.

He revisited them as well as others in his photos decades later, and learned that the girl in his picture would have her own family and continue to live in the same cemetery. In the same vein, Dematteis decided early on that he would return to Ecuador in 1993 and continue photographing the Texaco corporation’s oil exploitation and pollution well after the mainstream media had left.

The panel said that the news media’s unfavorable reputation will make people, especially authorities, even more resistant to working with the press. They referenced specific attempts from the military to control what gets published, and agencies using reported content to inject their own agenda.

They explained the importance of sticking with a story. Documenting people, war and poverty is a process that people unfamiliar with journalism may not be aware of, Komenich said.

When he needed a press pass to do coverage in San Salvador, he went to authorities for clearance and entered a room where a man was stamping papers.

“‘I just want you to know something — I am not here to provide bodies for your photographs,’” Komenich recalled the man saying. “And he looked me right in the eyes and almost cried. I was just another guy to him, out to get pictures of dead Salvadorians.”

The guest speakers said that despite people’s attempts to control the publication of information, it remains essential to capture what happens and to show it to the public as it is, while leaving it to viewers to decide how to respond.

Komenich added that organizations were built over the years to support the people that they saw suffering, such as a starving boy he photographed in the Philippines. The journalist’s job, he said, is to just show things as they are.

“I never made a link with the recording I do with videos and photojournalism, but it seemed obvious that there’s a strong connection with ethics, empathy and the importance of what you put in the work you do, and that really talked to me,” said Celine Wallace, who follows Dematteis’s work.