What a Second State Takeover of City College Could Look Like

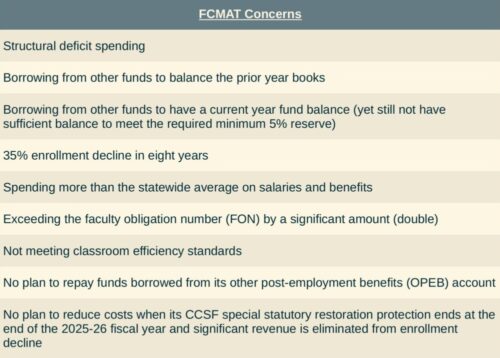

City College is once again facing the prospect of a state takeover in the wake of an April 7 letter from the state’s Fiscal Crisis Management Assistance Team (FCMAT), a California state-run fiscal oversight agency of public schools, which claims that City College is headed towards financial insolvency.

The letter states that high expenditures on faculty salaries and benefits threaten City College’s ability to stay financially solvent. Specifically, the letter says that the high percentage of money earmarked to pay faculty, pegged at 98%, means that the college cannot fund other expenditures, such as maintaining its facilities, which may undermine City College’s ability to serve its student body.

Balancing City College’s full-time equivalent student to full-time equivalent faculty (FTES/FTEF) ratio is a major agenda item for FCMAT, which states: “Correctly sizing its staffing for all employees will clearly be the largest factor in improving CCSF’s fiscal situation.”

The board has addressed this concern with cutting classes, but enrollment data shows the FTES/FTES ratio has not changed with class cuts. Malaika Finkelstein, president of the faculty union AFT 2121 said that the most recent FCMAT letter sounds like a rehash of the reasoning the state used to take over the college in 2013.

Rafael Mandelman, District 6 supervisor and former City College trustee, downplayed the possibility, saying the last takeover didn’t significantly benefit the state. “I think the last thing the state wants to do is to take City College over again.”

If insolvency occurs, FCMAT can take over the college, appointing a Special Trustee with Extraordinary Powers (STWEP) whose authority supersedes the college’s elected trustees.

Some claim, however, that the FCMAT’s findings are misleading, saying that expenditures besides salaries, such as maintaining the college’s facilities, are funded by Prop A, which was passed in 2012 and established a parcel tax of 1.1 cents per every $100 of assessed real property.

Some claim, however, that the FCMAT’s findings are misleading, saying that expenditures besides salaries, such as maintaining the college’s facilities, are funded by Prop A, which was passed in 2012 and established a parcel tax of 1.1 cents per every $100 of assessed real property.

“They fail to recognize that we do have funding for maintenance, it’s from our bond,” said Student Trustee Vick Van Chung.

Mandelman said that the previous takeover negatively impacted enrollment further, exacerbating the insolvency risks that the state used to justify the takeover in the first place — enrollment data from the Integrated Postsecondary Education Data System shows that between the 2012-2013 and 2016-2017 academic years, the number of full-time equivalent students at City College dropped by 38%, from 19,917 to 12,373.

“City College emerged … significantly damaged by the whole experience in terms of enrollment numbers plummeting, and the [subsequent] financial problems were only exacerbated by this process,” Mandelman said.

Others however, remember things a little differently.

Steve Ngo, who served as a trustee alongside Mandelman during City College’s state takeover, said that he remembers local authority of department chairs and faculty committees, both of which have a large say in the day-to-day of how City College is run, being largely intact during the tenure of both STWEPs.

“I don’t think, internally, governance changed that much. You still had faulty leadership, faculty governing committees … administrators had to consult with different constituent groups and develop policy, bring it before the chancellor and the board, and there would be a public hearing that would consider these policy changes in the same way that a board would.”

Ngo said that having a STWEP’s authority supersede an elected Board of Trustees was not a good thing, but that there were questions about whether the college was even capable of saving itself without state intervention.

“[The public] would try and persuade this one individual on whether a policy change or decision should be made or not,” Ngo said. “Obviously, that’s not the same as having a board elected by San Franciscans decide which policy to adopt or reject … but by that point there were concerns about keeping the college open and whether or not the board was up to making the decisions it needed to make.”

According to Wynd Kaufman, an engineering professor and president of the faculty union during the first takeover in 2013, Robert Agrella, the first STWEP at City College, introduced a policy requiring students to pay for their classes before the start of the semester in late 2013.

This policy was ultimately suspended, but automatically dropped more than 9,000 students from courses over four semesters, ultimately costing the college more than it saved — the college’s funding is primarily determined by how many students are enrolled.

Kaufman added that 2012’s Prop 30, which from 2012-2017 provided billions in tax revenue to fund public education, including $100 million for City College, helped ameliorate City College’s financial losses stemming from the state takeover. These funds also allowed the college to grow its student headcount at a rate faster than normally allowed by the state, helping to boost City College’s revenue.

According to Mandelman, the need for legislation providing emergency funding made evident the need to “recognize the rough road that the college was [on and] to allow the college, if possible, to quickly recover.”

Finkelstein said that a state takeover, and the subsequent appointment of a STWEP, would mean the disenfranchisement of the locally elected Board of Trustees, “which means [City College] being run by someone who’s not answerable to the community of San Francisco,” according to Finkelstein.

Miguel Quintero, who served as the student trustee during Compton College’s 2004 state takeover, said that although the college’s STWEP, Art Tyler, allowed the Board of Trustees to continue to operate, Tyler ultimately ran the show.

“The Board [of Trustees] could direct conversations, but at the end of the day, it was one person making decisions,” said Quintero.

The trustees are not alone in thinking that the looming layoffs will have an impact on the future of the college. Leslie Simon, a former City College faculty member who founded Project SURVIVE, a peer-training program run by the Women and Gender Studies Department that helps prevent domestic violence and provides counseling to domestic violence survivors, said that even if the layoffs help the college avert a takeover, they will damage the college as much as a takeover could, if not more.

“If these cuts happen, I’m not sure it will matter anymore,” Simon said.

Finkelstein echoed Simon’s remark, saying the loss of the board’s influence “doesn’t necessarily mean the policies the new [STWEP] would implement are dramatically different, if our local board is just gonna do exactly what the state wants anyway.”

John Rizzo, an incumbent trustee at City College who also served at the time of the first takeover, said the board is expected to avoid another takeover with a balanced budget and 5% cash reserve, which Rizzo said he expects will be passed by the Board in June.

Chung however, said that class cuts, which have often centered on preserving certificate, transfer, and associate degree programs, could also suppress enrollment and further marginalize students who are formerly incarcerated, foster youth, and/or domestic abuse survivors.

Finkelstein believes increasing enrollment would simply take investment in the future. Such investment may be coming from the Board of Supervisors, several of whom, including Gordon Mar and Hillary Ronen, have said that they will commit to supporting emergency funding for City College, although no such legislation has yet been introduced.

Mandelman said he expects the city to vote in favor of additional emergency funding, in part so City College can continue to offer non-credit programs which serve marginalized communities, such as ESL and Project SURVIVE.

“The city should put its money where its mouth is,” Mandelman said.