Sexual Assault: ‘Yes means yes’ bill clears California Legislature

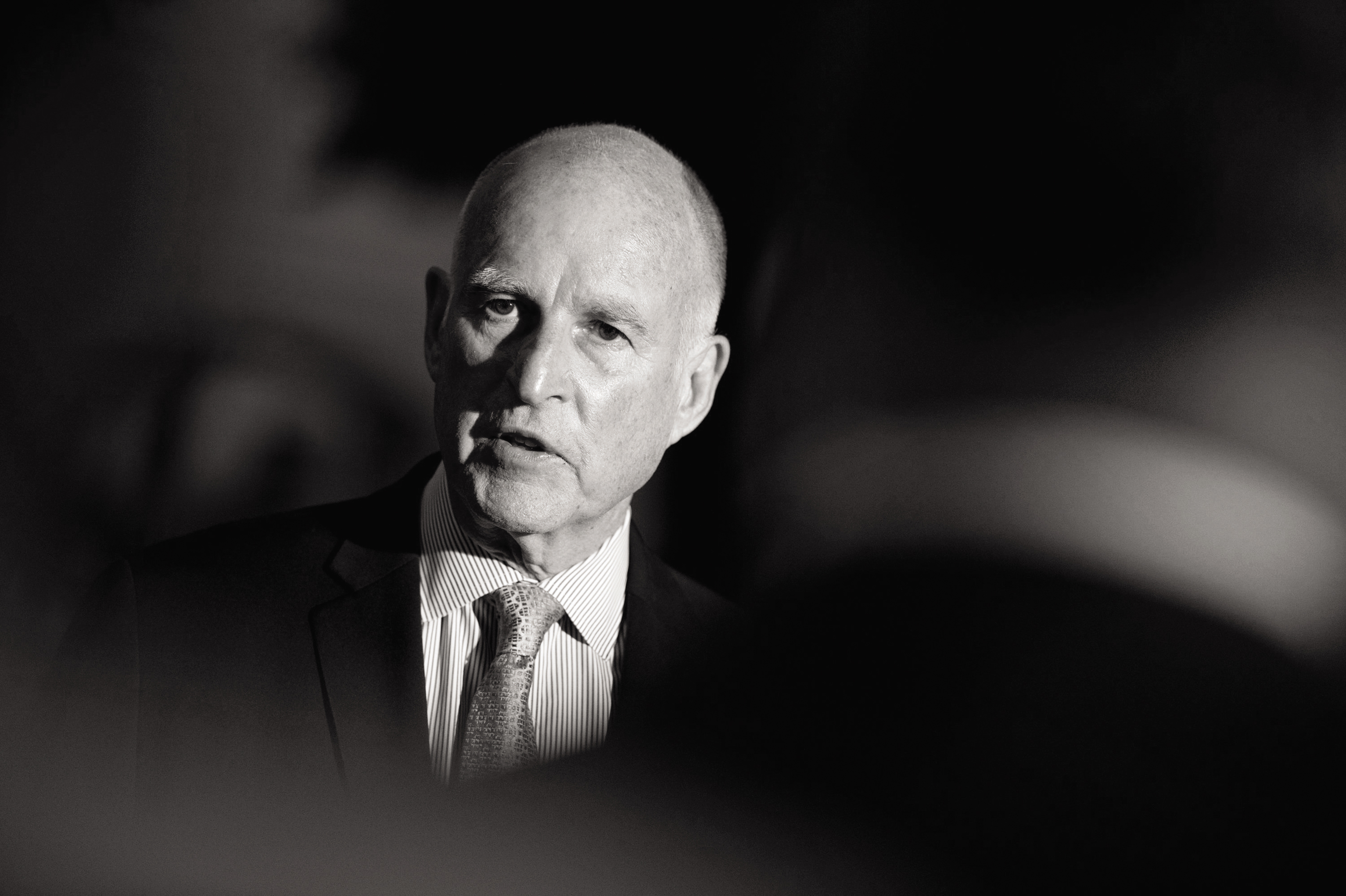

Gov. Jerry Brown talks to reporters outside the Old Governors Mansion on election night in Sacramento, Calif., Tuesday, June 3, 2014. (Jose Luis Villegas/Sacramento Bee/MCT)

By Katy Murphy

Oakland Tribune/ MCT

Yes-means-yes should replace no-means-no as the standard for sexual consent, or the lack of it, on California’s public and private college campuses, the Legislature decided Aug. 28.

Senate Bill 967 would require all colleges taking student financial-aid funding from the state to agree that in investigations of campus sexual assaults, silence or lack of resistance does not imply a green light for sex, and that drunkenness is not an acceptable defense.

“It does change the cultural perception of what rape is,” said Sofie Karasek, an activist who has fought for changes in UC Berkeley’s practice. “There’s this pervasive idea that if it’s not super violent then it doesn’t really count.”

California’s unique legislation comes amid a national movement demanding solutions to a problem that has plagued campuses for generations.

In the past two years, college students, alumni and the U.S. Department of Education has challenged colleges to do more to prevent attacks, educate students about consent, support rape victims and discipline offenders as federal anti-discrimination laws require.

Gov. Jerry Brown has until Sept. 30 to sign the bill and generally does not comment beforehand.

“If the governor signs it, this will lead the entire country, the nation,” said the bill’s sponsor, Sen. Kevin de Leon, D-Los Angeles, who called the approach a “paradigm shift.”

“It’s very difficult to say no when you’re inebriated or someone slips something into your drink,” he said.

The “affirmative consent” standard in the bill makes everyone responsible for ensuring in advance — verbally or non-verbally — that a sexual act is desired. The traditional no-means-no standard, the bill’s supporters argued, unfairly burdens victims by making them prove they had clearly conveyed that they did not want to have sex, but that it happened anyway.

Twenty years ago, the idea of gaining explicit consent before engaging in sexual activities was considered so extreme it was — literally — laughable. Saturday Night Live in 1993 lampooned the consent policy adopted by Ohio’s Antioch College with a game show titled “Is It Date Rape?”

“May I elevate the level of sexual intimacy by feeling your buttocks?” the male asks.

“Yes. You have my permission,” the woman replies.

Since then, the affirmative approach has gained so much acceptance that many campuses, including private schools such as Santa Clara University, now use a similar standard. They say the bill, which also requires outreach and prevention programs on assault, dating violence and stalking, would require only a tweak in their policies.

The UC system rewrote its sexual assault policies in the spring to that effect; all three of the state’s public college systems back the bill, and no colleges officially opposed it.

The legislation does have its critics. A Los Angeles Times editorial said it would be “extremely difficult and extraordinarily intrusive to micromanage sex so closely as to tell young people what steps they must take in the privacy of their own dorm rooms.”

But the bill’s proponents say those who think seeking consent is awkward, unrealistic or mood-killing miss the point.

“If I’m with another person, I always check in to make sure they’re comfortable,” said Meghan Warner, a Cal junior who founded Greeks Against Sexual Assault and leads training on consent. “It doesn’t have to be like, ‘Hello, will you sign this bedroom contract?'” she said. “It’s an ongoing conversation.”

Still, some are uneasy about the legislation, and argue the existing legal definitions of rape should suffice.

The new rules will lead to “too many punitive situations” for young men, said a spokesman for the San Diego-based National Coalition for Men.

“Of course I agree that people should actually consent, but the world doesn’t work that way,” said J. Steven Svoboda. “There’s no way to legislate the ambiguities away.”

The American Council on Education also has expressed concern. “I think that one needs to understand that both ‘yes’ and ‘no’ have specific meanings, but that they aren’t always going to be expressed quite so clearly when there are young people who are engaged in activities,” said its general counsel, Ada Meloy.

The standard could be tough for universities to implement, said UC Hastings School of Law Professor and Provost Elizabeth Hillman. Colleges need to promote respectful and responsible sexual behavior, she said, but they aren’t equipped to investigate all sexual assault complaints — and the new law could make that task more difficult.

“I think we are making progress,” she said. “There’s just a risk of going too far and having negative effects instead of positive effects.”

But some say that even if imperfect, the legislation sets an important standard: knowing — not guessing — whether your advances are desired. “It gives you less of an excuse to say, ‘I didn’t know,'” said E. J. Morera, a Cal freshman.

Does the prospect of being unjustly accused — and disciplined — under such a policy make him nervous? “I feel like if it makes you nervous,” he said, “I think you’re doing something wrong.”