Folsom Street Fair consent policy creates discussion around photography rights

By Adina J. Pernell

apernell@theguardmsan.com

Stretching across 13 city blocks,the Folsom Street Fair in San Francisco is the world’s largest leather event, drawing leather culture enthusiasts, and tourists alike, and has become a major influencer in informing the public about sexual culture that strays left of mainstream.

It has long provided a space for members of the kink community, including those of LGBTQ and Bondage, Dominance, Sadism and Masochism (BDSM), to express themselves openly through live fetish demonstrations. Participants often wear fetish gear and nudity is welcomed.

Naturally, the Folsom Street Fair attracts media outlets, reporters, photojournalists and street photographers, both amateur and professional, looking to capture a visual record of the event.

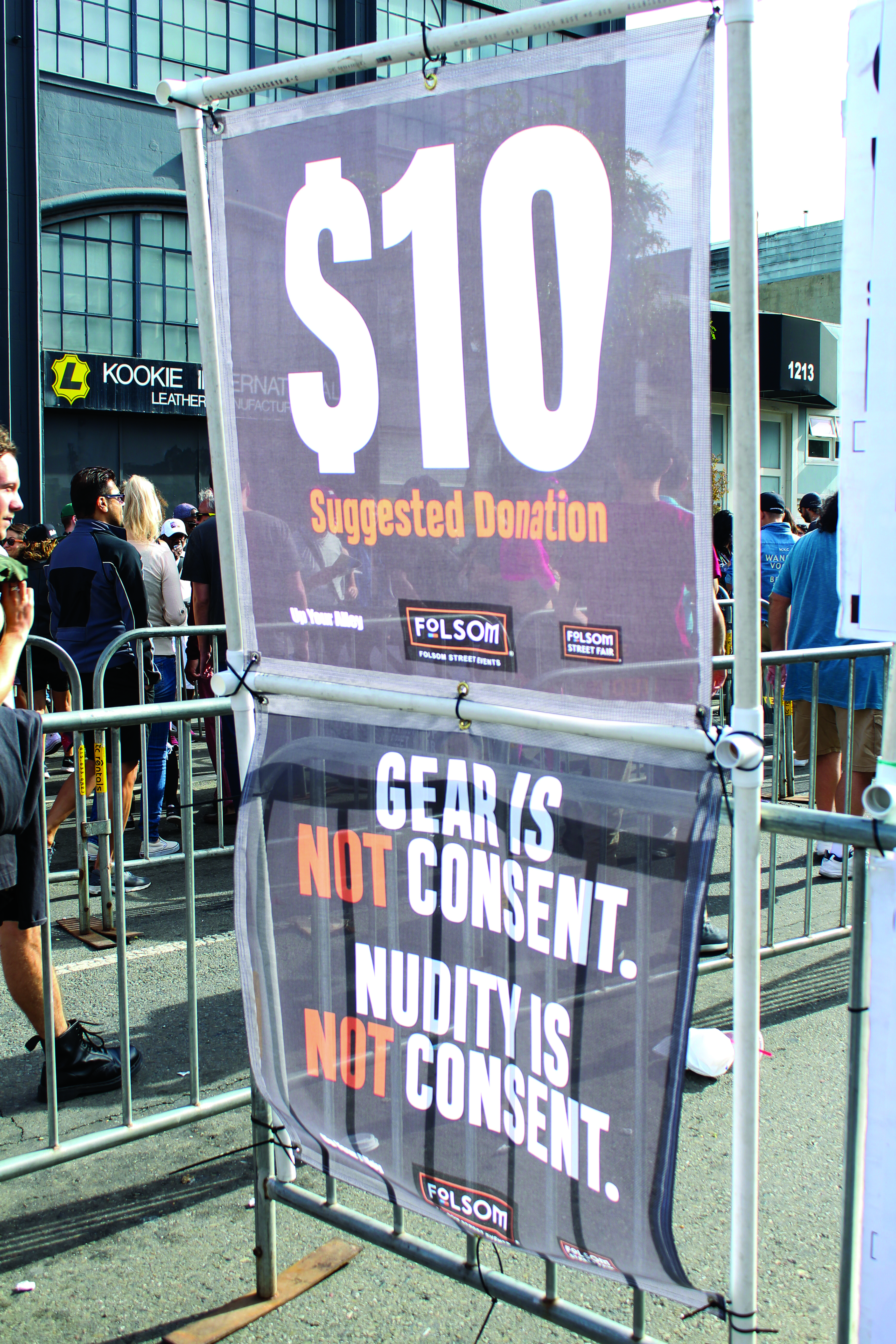

This year the Folsom Street Fair ran a campaign highlighting the importance of consent. At fair entrances visitors could see large signs that read “Gear is not consent, nudity is not consent”. On flyers distributed throughout the event the slogan is repeated along with the admonition to “ask first before photographing or touching someone. No means no.”

“We are fully aware that it is legal to photograph people on a public street also at a public event,” said Patrick Finger, Executive Director of Folsom Street Events. “We’re simply asking that people ask first before they take pictures because it’s a simple matter of respect,” said Finger.

A coordinator for the Society of Janus (SoJ), the largest BDSM organization in America, who goes by the name Frey said that although SoJ doesn’t have an official policy on photography and consent they are “going along with the message of Folsom Street Fair because [they] think it’s good idea.”

Frey said that SoJ also recognizes that legally people often have the right to photograph, which Frey admitted, is kind of a separate question. “It’s definitely a nuanced discussion to have,” said Frey.

Sex worker, activist and former City College student, Maxine Holloway who started the campaign Ask First in 2014 after being groped and sexually harassed at the Folsom Street Fair in the past said, “I’m happy that the fair is getting on board with the consent issue. It’s about damn time.”

Regarding the photography policy at the Folsom Street Fair Holloway echoed the sentiment of the flyers. “Consent isn’t just about sex. I would love to have a choice in the matter and know my picture is being taken,” Holloway said.

Concerns and Rights

But among the photography community, there is concern that the very nature of the statement made in the posters seemed to lump the failure to request a photograph at a public event into the same context as sexual assault.

“The issue I have, is that touching and photography have been bunched together,” said freelance photographer and City College student, Nathaniel Y. Downes. Downes also was disturbed by the fact the sign mentions photography before unwanted touching, saying it was, “almost as if they’ve prioritized that photography is worse.”

“I’m sure that’s not the intent — that they didn’t mean to put it in an order that made it in some sort of hierarchy,” Downes added, “but either way they did put them both together, and as a photographer, I don’t think taking someone’s picture should be related to sexual harassment… Sexual harassment is a very negative thing and it shouldn’t be happening. But taking a picture is something that I do for a living.”

Downes worried that people might come to the conclusion that the issue of photography consent and sexual assault are related.

When asked about how the statement might be interpreted, Finger said, “No way are [we] equating or comparing the two. But we are equating both [photography and unwanted touching] with consent and respect.”

Some view the Folsom Street Fair statements about photography as a step toward press censorship and contrary to the First Amendment that provides for the rights of a free press, including photography at public events.

“Once you say you can’t photograph at our [Folsom Street Fair], other places might follow suit,” said Downes.

“I strongly believe that taking photographs of things that are plainly visible in public spaces is a constitutional right, and so do the courts and organizations like the American Civil Liberties Union (ACLU) and most news organizations,” said Ken Light, Reva & David Logan chair and professor of photojournalism at the Graduate School of Journalism, UC Berkeley. In an email response Light said, “I have seen in recent years individuals that have felt that photographers have no such rights.”

According to the ACLU, “taking photographs of things that are plainly visible from public spaces is a constitutional right.”

“It is a slippery slope and abuse of power when we start to censor and intimidate photographers who are legally [expressing what] our constitution and laws allow,” Light said and added that “in this era of Trumpism this slope is ever more slippery. Journalists and photographers are already under attack, we must stand up and protect our rights, as hard as it is for some to understand.”

On August 30 an incident at a Trump rally went viral when a volunteer was caught putting his hand in front of a photographer’s lens to prevent the photographer from taking a picture of a protester who was being removed from the event. The Trump administration removed the volunteer from the campaign process, but the actions that could intimidate and prevent photojournalists from covering public events may still persist.

“A [month] before Homeland security [ran a campaign saying that] photography may be a sign of terrorism,” said Downes. “The President said that journalists are the enemy of the people.”

In light of this criticism from Homeland Security, President Trump and others, Downes worried what this might mean for the future of photojournalism and journalism. “It starts changing our norms to where photography becomes a negative thing” Downes said.

The Issue of Privacy

Photographers also want to protect the journalistic value of their images by not taking pictures that might end up looking contrived.

“While I understand why we value photography that isn’t staged, [we need to ] examine what is ethical,” said Holloway. “I’m going to err on the side of people feeling safe and having fun at the Fair, especially in a [sexually] fetishized environment.”

Given that Folsom Street Fair has thousands of attendees each year, coupled with the fact that many of the participants of the fair are in various states of undress, it is understandable for fair-goers to want to have a relative amount of control over their image. The very act of being at the Folsom Street Fair could pose a risk to the career of someone in a field where conservative views on sexuality are held.

Finger mentioned that when the Folsom Street Fair policy was created the organizers of the event took into consideration that some people might not want to be “outed”.

“We get a lot of people coming from Red states and areas that really aren’t that liberal. It’s really difficult for them to be out as a LGBTQ or straight people that are in the leather community,” said Finger. “They are able to walk down the street in the middle of the day. We’ve created a safe space for them. But if they’re photographed it’s no longer a safe space,” Finger said.

The reality though is that the Folsom Street Fair is in a public, crowded area and any person could come along with a camera phone. Even if they take a wide-angle shot, they might capture someone who doesn’t want to be seen in attendance.

“I’m no lawyer, but I’m a working photographer, and I always have had the understanding that unless it is at a private event, or anywhere you have a reasonable right to privacy such as a bathroom, you can photograph anything that you can see with the naked eye,” said Jessica Lifland, a freelance photographer and Photojournalism instructor at City College.

According to Lifland scenes of public nudity don’t affect that right, but she emphasized that although photographers “have the right to [photograph [someone], they can choose not too,” depending on the circumstances.

Online Photo Editor at San Francisco State University, Douglas Zimmerman, made such a choice. “I remember when I photographed the Folsom Street Fair on assignment. This lady was getting whipped out in public and she didn’t know her tolerance for pain. There was a point when she was really in pain. Someone requested me not to take her photograph,” he said “I could see that she was really in pain and that it was a private [moment] for her.” Faced with that realization, Zimmerman stopped taking photos of the woman.

The right to photograph someone doesn’t bar a photographer from using compassion and ethics when taking photos of people or the responsibility to be sensitive to the context of the each situation they are seeking to portray.

The code of ethics section on the website for the Society of Professional Journalists (SPJ) states that photographers need to “balance the public’s need for information against potential harm or discomfort,” and realize that the “pursuit of the news is not a license for arrogance or undue intrusiveness.”

“I think it’s up to the photographer to have empathy and an understanding of what’s ok and what’s not,” said Zimmerman of his judgement call. He also acknowledged that while he can understand the Folsom Street Fair’s position and that while he felt “their intent is good”, their photography policy “might be a little heavy handed.”

“I don’t know what the right way to handle [the photography policy] would be. I think it’s going to be an ongoing concern and an ongoing problem,” said Zimmerman.

“While I believe their intention is honorable and they want to protect individuals who might exhibit behavior and or participate in activities that they want to keep private,” said Light, “in a public place any activities can be photographed, and I vote for freedom of the press.”

“There needs to be a conversation. We haven’t examined what street photography in the digital age can mean,” said Holloway.

While campaigns such as Ask First and statements like the ones made at the Folsom Street Fair are creating much needed dialog around sexual consent, the verdict is still out as to whether the accompanying sentiments about photography consent may be instilling an attitude of fear and suspicion toward legitimate photographers, and if other public events adopt similar policies what this could mean for the future of photojournalism.