And The World Stood Still

By Casey Michie

I recall close to a decade ago when the immediate world around me seemingly stood still, if only for a moment. It came in the form of darkness; the greatest blackout California had ever seen. For twelve hours the daily routines of modern life halted as technology went dark and the streets came alive with conversation as adults sat drinking beers and children played aimlessly through alleys.

I bring this up not because it was necessarily a profound moment in time, for many of us the night has been largely forgotten. No, I bring it up because it offered a small glimpse into another way of living. Of a life not dictated by monotonous routines or evenings dominated by television. Of brief hours where neighbors disposed of distractions and interacted honestly with neighbors.

It seems we’ve become so accustomed to the routines of modern life. Accustomed to the long hours and the rush hours and the deadlines that invade further into our consciousness each day. Shouldn’t there be more to life?! We have become so accustomed to the trajectory of the world, that we rarely take a moment to consider that the trajectory could ever change.

And yet now it has.

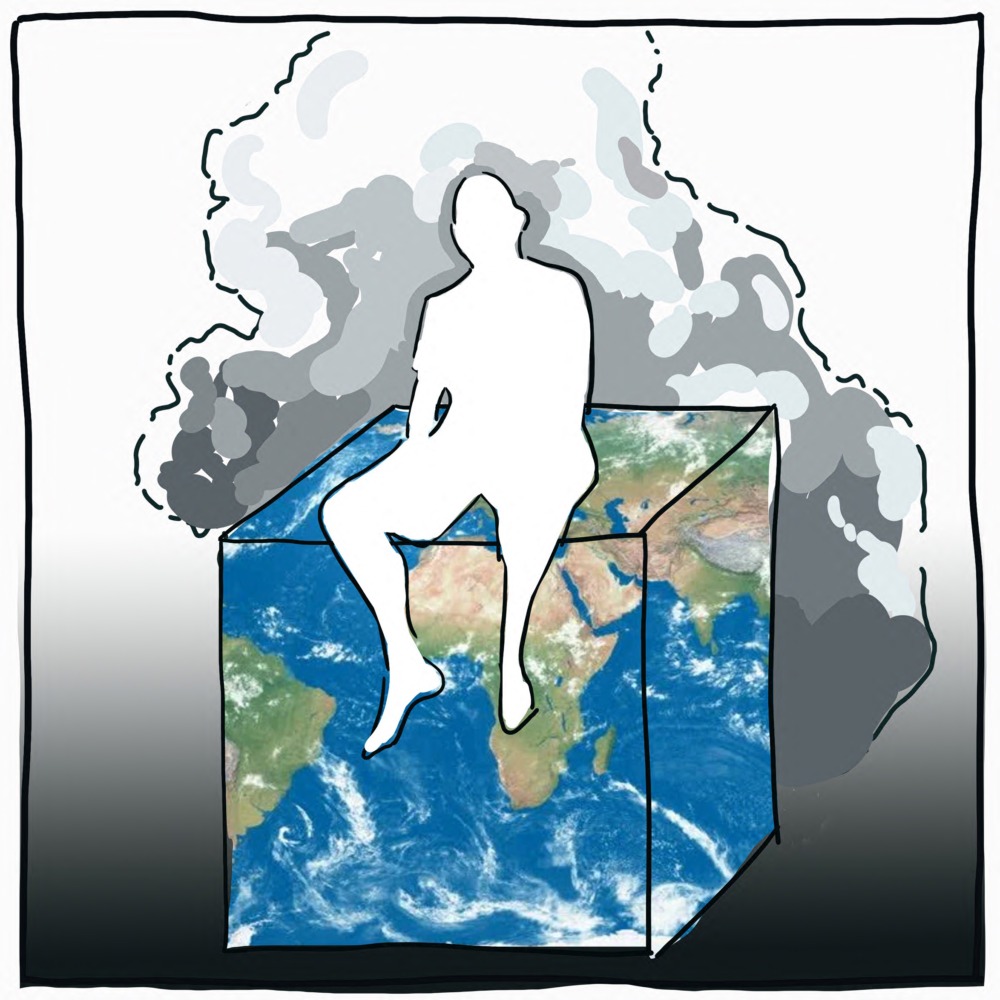

For the first time in generations, we have seen society come full stop in a matter of weeks. A full stop that affects not a single region but the entirety of the world. The pandemic has changed the course of our daily lives, and the important question we must ask ourselves now is: why did we live the way we used to?

I am not talking here of political revolution, but a revolution of cultural introspection. The pandemic has shown us that the monotonous tread forward of society is not set on unalterable rails. That the tribulations of our modern world are a construct of our own making. And as we trade old uncertainties for new, it has undeniably shown us that we are all in this together.

The thought brings to mind an idea of Walker Winslow that Henry Miller recounted in his essay entitled “The Hour of Man”. The piece was written some 80 years ago but holds weight, even to a greater magnitude now, to our lives today. Winslow writes,

“I want to see the radio or television turned off for an hour a week, the paper or magazine laid aside, the car locked safely in the garage, the bridge table folded, the liquor bottle corked, and the sedatives kept tightly in their packages. I want to see production and consumption forgotten for this hour. Politics must be forgotten, national or international. The hour that I propose could be called The Hour of Man. During this hour man could ask himself and his neighbor just what purpose they are serving on earth, what life is, what a man or woman can rightly ask of life as well as what they must give in return.”

It is indeed a romantic thought: to come together for a short moment to meditate on what it is to be human. To meditate on what it is to be part of a community.

The pandemic, in its own way, has offered us a form of this introspection. It has given all of us an opportunity to question the way we used to live. To ask ourselves what it means to be a worker, a neighbor, a lover, a friend. Through the isolation, the hardship, and the loss, the pandemic has also given us an opportunity to grow.

As society goes dark around us, there is light to be gained in the perspective of its absence. Our communities and our world will emerge from this pandemic vastly different from how it entered. It would be a tragedy otherwise. In this moment, in this interim of normalcy, we have a chance for introspection. This is our chance for The Hour of Man. Our chance to consider what we want our world to look like as it inevitably starts spinning again.