Into The World of Dr. Seuss: Pulitzer Prize Winners, Theodor Geisel and Jonathan Freedman Connect Over Literature and The Whos of This World

By Liz Lopez

At the very top of Mount Soledad in San Diego, overlooking the Pacific Ocean, lived the famous writer of children’s books, Theodor Seuss Geisel, better known as Dr. Seuss.

In spring 1984, Jonathan Freedman, who currently volunteers as a writing mentor with the City College English department, was a relatively unknown young journalist, and a runner-up for the Pulitzer Prize for his editorials in The San Diego Tribune. His editor, Neil Morgan, was friends with “Dr. Seuss” and asked Freedman to write a piece about the famous author, who was turning 80 and dying of throat cancer.

Freedman’s editorials usually dealt with serious issues surrounding immigration that included the viewpoints of immigrants, border patrol agents, and U.S. business owners. This was a much different subject for him, Freedman said.

When asked to do this story, Freedman was reminded of how much he hated reading as a child, but he really loved Dr. Seuss’ books. So, before heading up Mt. Soledad, Freedman stopped by a La Jolla bookstore and bought every Dr. Seuss book he could find. He was both nervous and excited to meet the man who wrote these books.

Meeting Dr. Seuss

A tall, polite man with rectangular glasses greeted Freedman at the door. It was Theodor Geisel himself who invited him in. Freedman recalled he had high eyebrows that waggled when he spoke; his eyes – magnified by thick eyeglass lenses – evoked kindness and made the young reporter feel immediately at ease.

“We sort of hit it off. He told me his life story and it didn’t last a half-hour; it lasted all day,” Freedman said.

Geisel’s home looked like it was straight out of a fairy tale, complete with a castle-like tower. Freedman recalled feeling like he was in a large eagle’s nest, perched high upon a cliff. From the window, Freedman said he could see seagulls flying below him and the surf rolling in. The rooms were spacious with floors made of natural wood tiles. Hanging on the walls were one to two foot tall taxidermy-like sculptures that appeared to be peculiar Dr. Seuss creatures. They were not necessarily characters from his books, though they were all hand made by Geisel himself.

Freedman, being a new father, was surprised to learn that Dr. Seuss had no children. “You raise them – I’ll entertain them,” Geisel was fond of saying.

Theodor Geisel

Geisel’s father had emigrated from Germany and became Superintendent of Parks that included running the local zoo, in Springfield, Massachusetts. When he was a child, he liked to go to the zoo with his dad to visit and sketch the animals.

Geisel attended Oxford University in the 1920s. He studied Shakespeare and he learned about iambic pentameter. According to Freedman, Geisel would sit in class, totally bored out of his mind, taking notes and doodling animals from his father’s zoo. The elephant became “Horton,” and other storybook characters also started out as doodles. He showed Freedman some of those doodles, laughing as he did. Freedman warmly recalled the 80-year-old man reflecting back on his life and his work.

In Dr. Seuss’ book “Horton Hears a Who!” Horton the elephant was bullied and tortured for trying to protect the small people of Whoville. He appeals to the people of Whoville: “Don’t give up! I believe in you all: A person’s a person, no matter how small.”

Horton called on these small people (called Whos) who are not being seen or heard, to rise up and make noise so loud that even the powerful could not deny hearing them. In our present political climate, this sentiment rings true today more than ever. The conversation between Geisel and Freedman was not a superficial one. They connected on another level, like only two great writers could, both destined to change the world.

Although Geisel and Freedman were 50 years apart, they shared many similarities beyond writing; both deeply cared about people, politics and the environment.

Jonathan Freedman

The two were also well traveled and they spent time talking about their adventures. In 1973 when Freedman was in his early 20s, he assembled a group of friends and traveled throughout Latin America. On the day they were supposed to cross from Bolivia to Chile, General Pinochet had just overthrown the government of Salvador Allende and the border into Chile was closed, so he re-routed to Rio de Janeiro.

A chance encounter on the beach of Rio led Freedman to secure a job as a foreign correspondent at a news service called Associated Press (AP) and he wrote stories that were transmitted around the world. That was the beginning of his journalism career.

“I did write fake news once,” Freedman confessed. “I was on the night shift, sitting in a lonely, hot office . . . when a telex came in from a newspaper in Rio and it said, “Today a shipload of animals for the Rio Zoo is coming from Africa.” So, I wasn’t just content to write the AP story. I don’t know what got into me, but I started pretending to interview all the animals and get quotes from the giraffe, the zebra, the tiger, and the lion . . . and it was sent out to AP headquarters in NY.”

The next day, when Freedman turned up for work, the Bureau Chief called him into his office. He had gotten an urgent message from the head of AP that said, “Interviewing the giraffe? Indeed! Who is Freedman and why is he working at AP?” . . . ,” chuckled Freedman, who left Brazil in 1976. Seems Dr. Seuss was not the only one intent on personifying animals.

Not having been to Brazil, Geisel asked if Freedman knew his Brazilian cousin. Freedman thought for a moment and quickly recalled that during his time in Brazil, the military dictator was President Ernesto Beckmann Geisel.

Dr. Seuss’ cousin was the president of Brazil.

“Was my cousin a very bad man?” Geisel asked. Freedman explained that the former president was responsible for torturing people who opposed the government, but was also the first leader, after multiple dictators, to say that he was going to open Brazil up to democracy.

Fighting Fascism

Prior to writing children’s books, Dr. Seuss was a political cartoonist and, due in part to his German heritage, he understood very early on who Hitler was and he did his best to warn Americans by exposing this threat through his illustrations.

Geisel’s opinions faced opposition from the “America First Committee” group, lead by pro-fascist and anti-Semitic members, who didn’t think the atrocities taking place in other parts of the world were any of their concern. The group was disbanded after the attack on Pearl Harbor.

Freedman’s writing included editorials about the nuclear arms race. Geisel of course was well informed and wanted to show him a draft of his latest book, “The Butter Battle Book”.

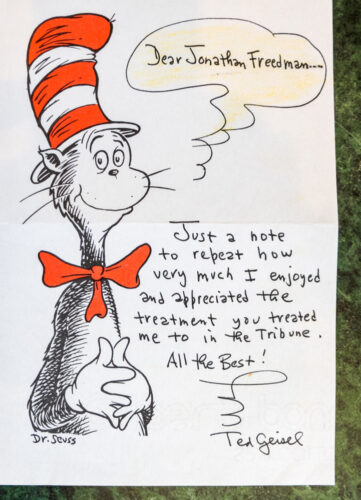

At almost 80 years old, Geisel wrote a serious book, an analogy for the nuclear arms race, as this was the time when the U.S. feared a nuclear war. Geisel made a copy of this book on his home Xerox machine and signed it for Freedman, along with all the other Dr. Seuss books that he’d brought.

Pulitzer Prize

As their conversation came to an end, Geisel seemed a bit sad and lamented over not having won any major literary awards during his long life as a writer, which shocked Freedman. This thought continued to swirl in Freedman’s mind as he drove down Mt. Soledad and back to his office.

The next day, unbeknownst to Geisel, Freedman called Columbia University and asked to speak to someone regarding the Pulitzer Prize. After explaining the situation, the Pulitzer representative said, “I’m really sorry Mr. Freedman, but they don’t have an award for children’s books.”

“But it’s Dr. Seuss!” Freedman exclaimed.

Just before the representative hung up the phone, she mentioned that there was a special award that was given once in a long while to artists who have made extraordinary contributions, but the recommendation needed to be made by a publisher and he was already late. Freedman said he promptly contacted his editor, submitted his story on Geisel’s 80th birthday and included a note that said, “I think we should get the newspaper publisher to nominate Dr. Seuss for a Pulitzer Prize.” The publisher complied.

On the day of the Pulitzer Prize announcement, Geisel called Freedman to tell him that he had just won the Pulitzer Prize and that he heard he had something to do with it.

Freedman said, “Tears were in my eyes because more than one generation had grown up with this. I was able to do something, totally by chance, that meant a lot to this man and, of course, it meant a lot to all Americans. Suddenly it wasn’t Dr. Seuss that was famous, it was [Theodor] Ted Geisel that was famous.”

SIDE BAR

Geisel passed away on September 24, 1991 after dedicating much of his life to the education and entertainment of children and leaving behind a legacy of literature that includes “The Grinch”, “The Lorax”, and “The Cat In The Hat”.

Freedman went on to win the Pulitzer Prize in 1987 for his editorials that influenced Congress to pass major immigration reform.

Today, Freedman hosts a weekly online writing workshop for students who want to become better writers. He urges students to get involved, to think about the larger issues we are dealing with in the world, and, most importantly, to get out and vote this November.

Freedman also recently authored a book entitled “Solito, Solita: Crossing Borders with Youth Refugees from Central America”. It is a collection of oral histories that recounts the dangerous journeys of young people fleeing their countries, away from violence and into the unknown.

As for his purpose as a storyteller, Freedman is quite clear; “My life as a journalist and author is about hearing the Whos.”