How Soul of a Nation continues to highlight the struggles and victories of the civil rights era.

By Jennifer Yin

In celebration of Black History Month, City College students had the opportunity to attend a free showing for Soul of a Nation : Art in the Age of Black Power 1963-1983, which is an internationally acclaimed exhibition organized by Tate Modern.

The exhibit is currently housed at the M.H. de Young Memorial Museum in San Francisco Golden Gate Park and celebrates Black artists during two polar decades when issues of race and segregation plagued institutions in both public and private sectors.

Many of the photography showcased in Soul of a Nation were members of the Kamoinge Workshop, a New York-based group of Black photographers. The first Kamoinge director, Roy DeCarava wrote how the main goal of the group was to, “reflect a concern for truth about the world, about society, and about themselves.”

Kamoinge continues to serve and support Black photographers to this day.

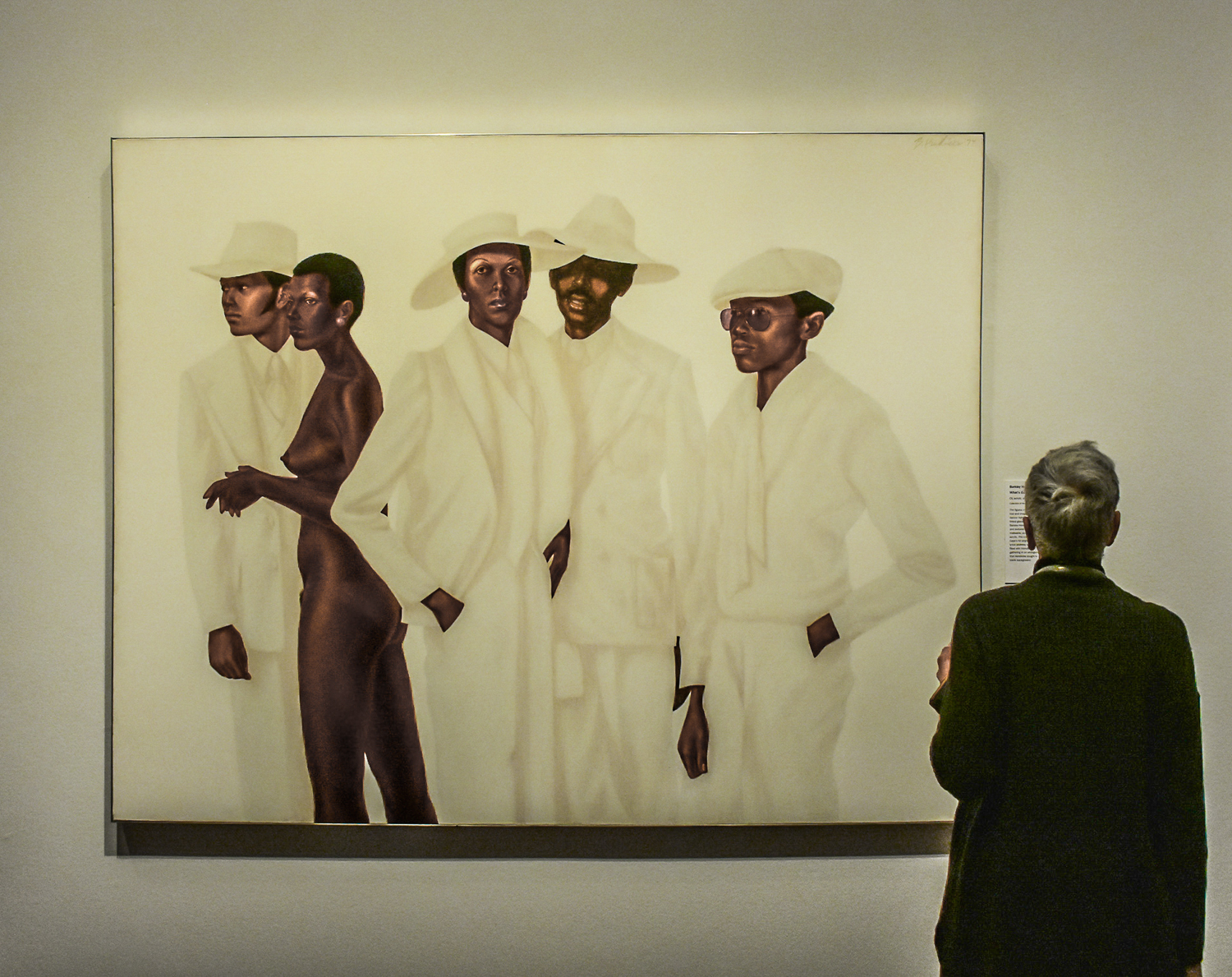

Soul of a Nation consists of a nine room gallery with each room representing a different era of the Civil Rights Movement. The opening room titled “Spiral” named after a group of New York artists from 1963.

For their one and only group exhibition the artists from Spiral decided to showcase their artwork in only black and white. However, with their diverse opinions ranging as wide as their artistic styles the different hues of blacks, grays, and whites symbolized their larger ideas of race.

One artist included in “Spiral” was Ming Smith, the first female member of Kamoinge. Smith’s core principle was, “the creation and dissemination of positive images of Black life.”

In her 1976 photo titled, “America Seen Through Stars and Stripes,” displayed a reflection of society on a storefront window with U.S. flags draped behind one solitary Black man. The man displayed in the image holds his composure and looks up towards the sky with the same reflection of society embedded into his sunglasses.

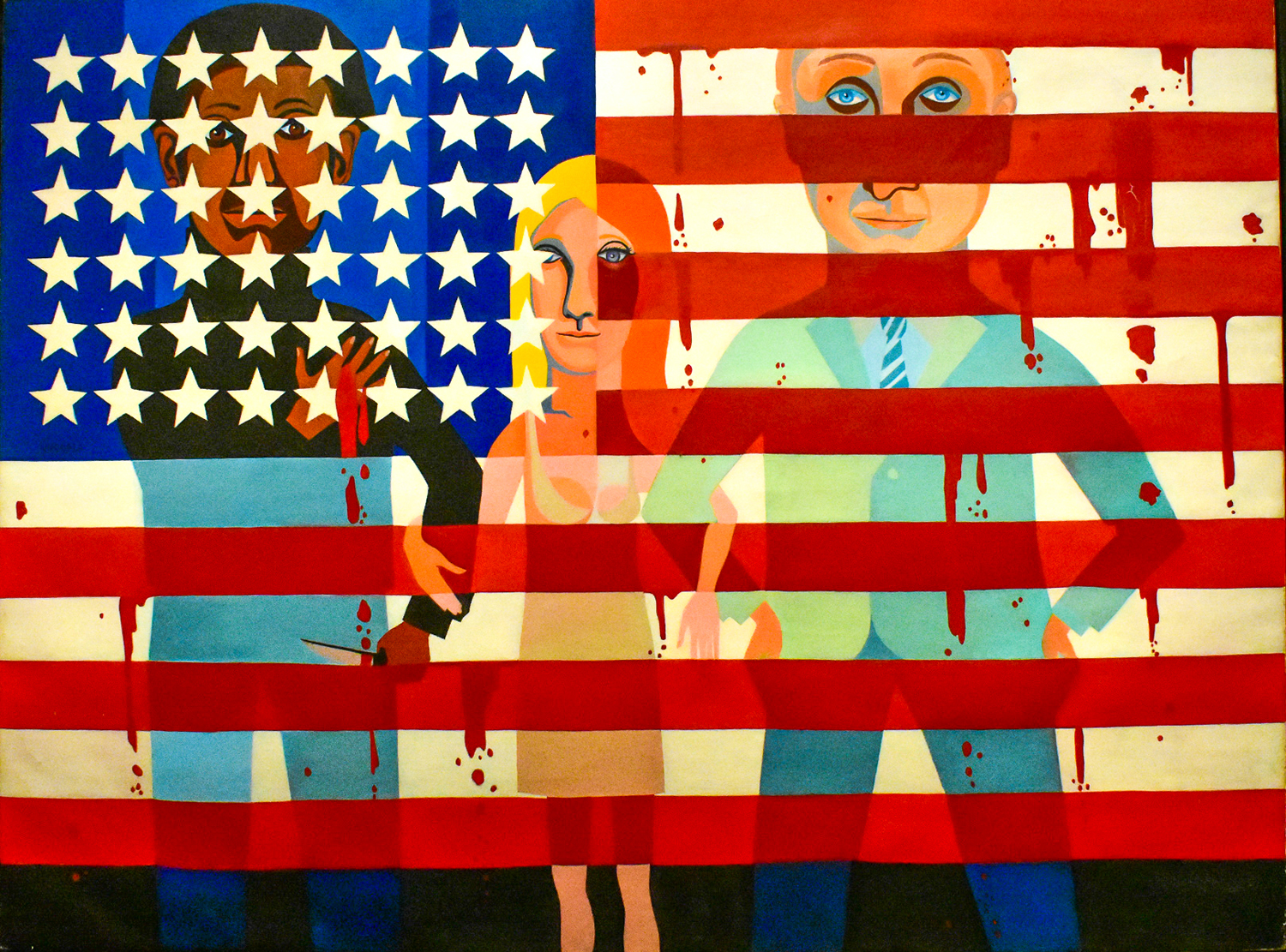

In the sixth room titled, “Message to the People: AfriCobra in Chicago,” included artwork from AfriCOBRA which was previously known as the Coalition of Black Revolutionary Artists [COBRA]. In 1968, AfriCOBRA members sought to bring art directly to the people and to create a community-focused philosophy and aesthetic of Black art to address social, political, and economic issues that supported the Black liberation movement.

Contrasting from “Spiral’s” black and white theme “Message to the People : AfriCobra in Chicago” displayed colorful paintings of revolutionary leaders such as Malcom X and Angela Davis.

Artist Wadsworth Jarrell created Black Prince in 1971, which paid homage to actor Ossie Davis’s eulogy for Malcom X, a black nationalist leader. David said, “Our own black shining Prince!” Jarrell’s posthumous portrait of Malcom X repeats the letter B for “Black” “Beautiful” and “Bad.” The portrait also incorporates empowering words once said by Malcom X. “I believe in anything necessary to correct unjust conditions-political, economic, social, physical—anything necessary as long as it gets results,” Malcom X said.

In addition to housing Soul of a Nation, the de Young Museum also offers tips on how to teach children about tolerance. Some advice the museum gives is to acknowledge the many ways people are different and to emphasize the positive aspects of our differences.

The museum also encourages families to discuss their own differences amongst each other and how these differences may have either helped or hurt them at times. They further added how finding similarities becomes even more powerful in creating a sense of common ground.

Soul of a Nation will continue to open its doors to the public until March 15, 2020.