1968: THE YEAR THAT CHANGED EVERYTHING

By Casey Ticsay

Commemorating the 50th Anniversary of San Francisco State’s student strike.

The United States – marked by the civil rights movement, political assassinations, and antiwar protests – was home to social and political unrest during the 1960s as communities sought to build an inclusive and just America that supported the needs of all marginalized people.

“We need a change in education. If we are ever going to be able to relate to our people in a real way… we ourselves need to change,” student activist Roger Alvarado said in an interview with KRON-TV over fifty years ago.

By November 1968, San Francisco State University became an epicenter of struggle, with students demanding equal opportunities for minorities, more diverse representation and historical accuracy in academia, and the establishment of a College of Ethnic Studies.

Class dismissed

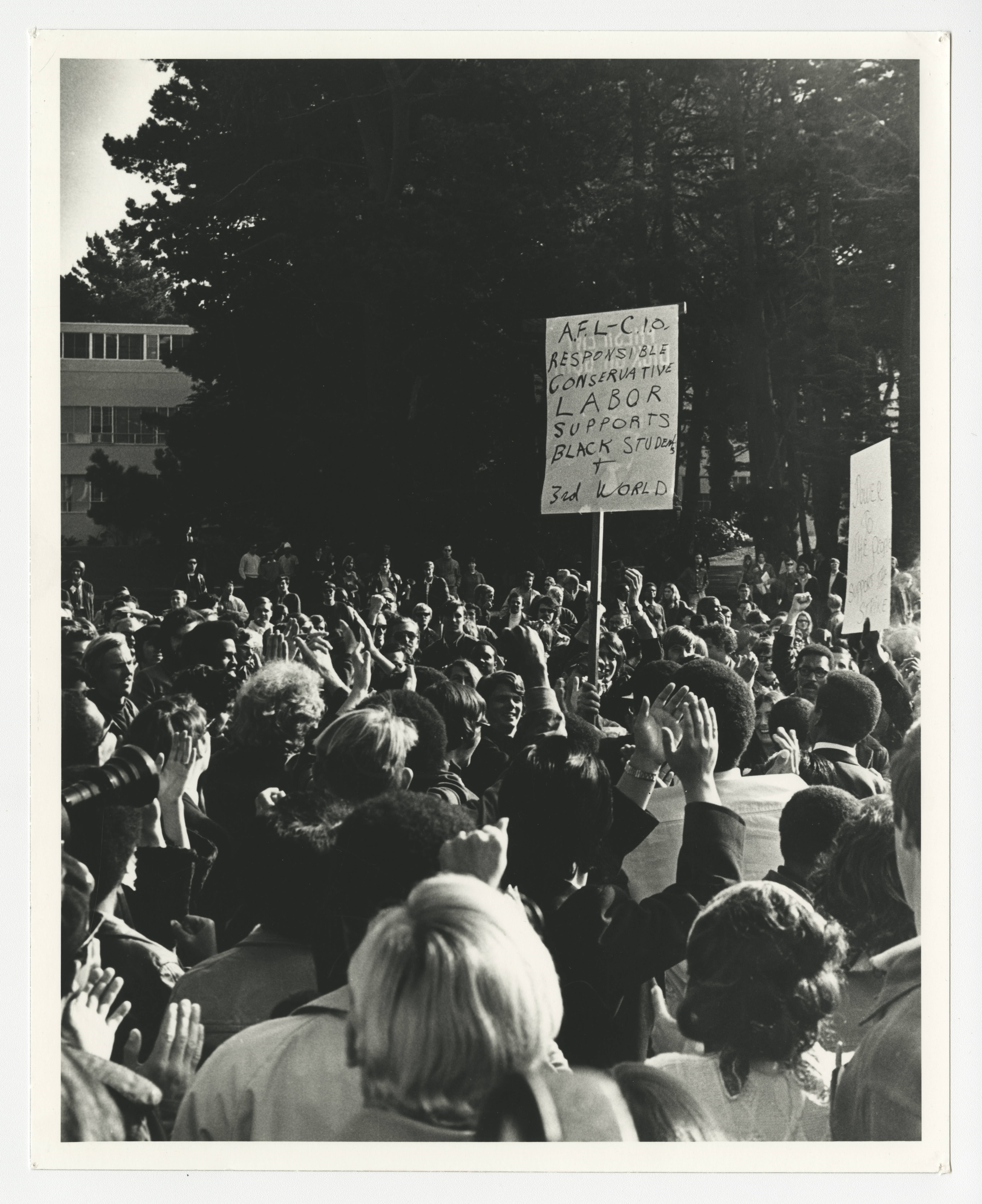

The strike unfolded over five months. Spearheaded by SF State’s Black Student Union and a coalition known as the Third World Liberation Front, it became the longest student-led strike in U.S. history, and laid the groundwork for similar college programs around the country.

The TWLF drew students from organizations across the college, including the Philippine-American Collegiate Endeavor, Latin American Student Organization, Mexican-American Student Confederation, Intercollegiate Chinese for Social Action, Asian American Political Alliance, and Native American Student Organization.

“We had the opportunity and we took the opportunities to establish relationships with people that we wouldn’t typically had been involved with as students,” Alvarado said. “It made it possible for us to call upon those relationships, gather the support, and encourage those to participate.”

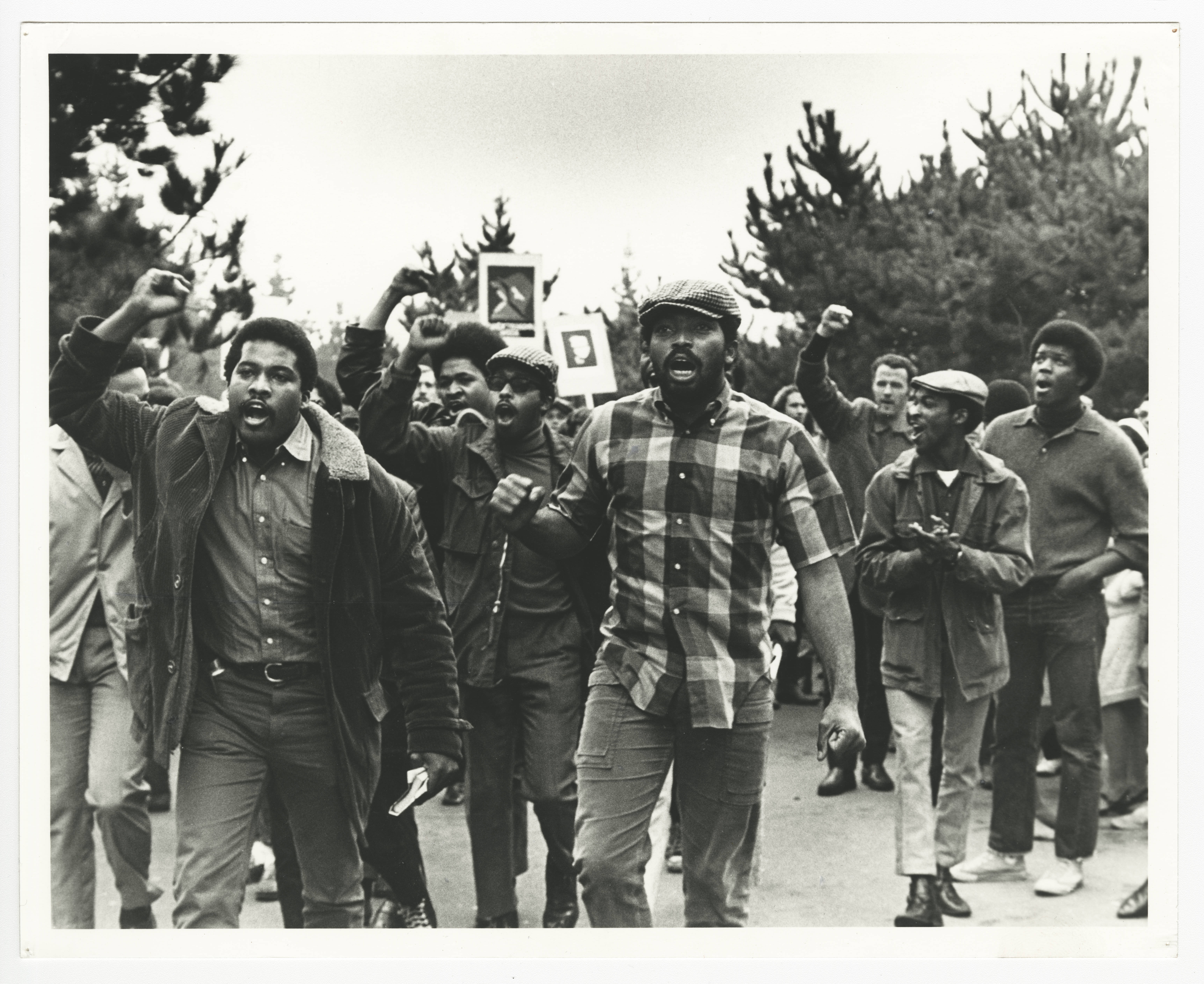

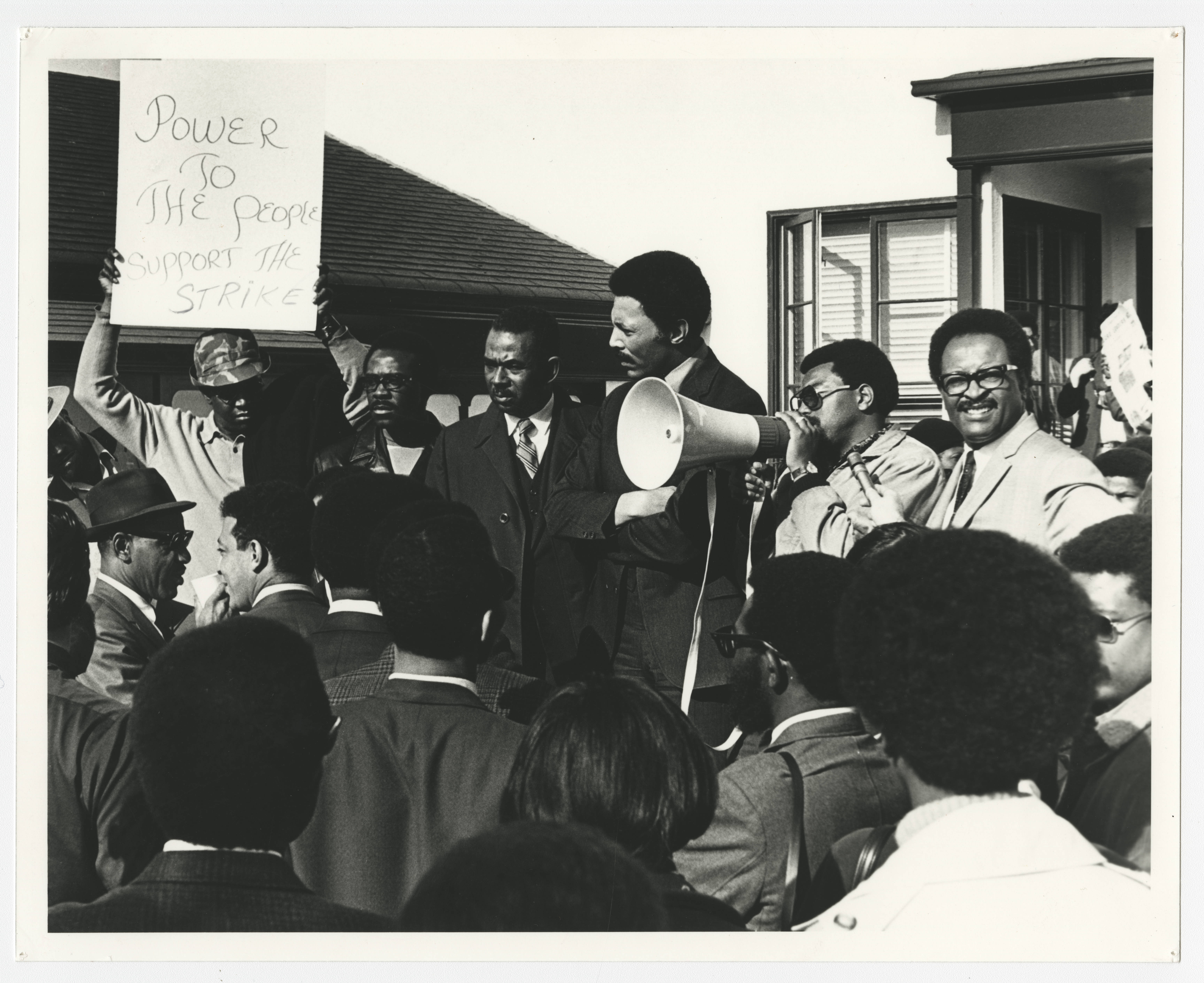

Students interrupted classrooms, arranged sit-ins, and held weekly demonstrations – determined to incite change in the state’s education system and continue the overall movement of liberation for all people.

“We wanted the American dream, but we weren’t experiencing it,” said Dr. Ramona Tascoe, one of the first strikers to be arrested during the campus protests.

Looking back, Tascoe noted the challenges students of color faced while living in a society that institutionalized racism.

“We were all struggling to assimilate or be who we were without being obvious that we were unable to take advantage of the opportunities that our brothers and sisters, who were white, had naturally. That was the reality of the day,” she said.

The fight for student power and autonomy shook the status quo and produced a wave of activism that permeated the city. Community members, along with the American Federation of Teachers, joined the strike in solidarity with student demands and educational reform.

Despite the added support, violence escalated as police attempted to quell the strike. About 500 protesters had been arrested by the time a settlement was finally reached on March 20, 1969.

While the agreement served as a foundation for revolutionary change, the struggle to uphold the right of all people to dictate their own destinies, on a variety of levels, was not yet over.

The fight for relevant education continues

Influences from the 1968 strike gave rise to several programs at City College, leading to the country’s first queer studies department and the creation of Philippine Studies, the only establishment of its kind.

“I wouldn’t be in college if the strike didn’t happen,” said student D’Andre Pope, who found his voice in a course that highlighted the diverse experiences of Asian Americans beginning in 1820.

Pope created “Ethnic Studies in Action” as a way to help mobilize students on campus and heighten participation within the community. The student organization provides spaces for learning and discussion, while calling for college curriculum that acknowledges the contributions different groups have made to American history.

“The oppression and the struggles of people of color cannot be boiled down to ‘all Asians have the same issues,’” Pope said. “There are names that survive and others that are lost in the writing of history, which is why we must preserve the narratives of every individual community.”

According to Pope, a lack of respect and general investment in the field of ethnic studies is nothing new.

“It’s always going to be a constant struggle. We need to keep fighting to grow diversity classes, not just try to protect the little we already have,” he said.

Departments across the board have faced various setbacks amid extended retirement incentives for employees and administration’s plan to reduce the number of course offerings over the next five years.

Meanwhile, some faculty and students question the direction City College is headed as it transitions to California’s new student centered funding formula, which provides additional revenue to community colleges that produce more transfer degrees and certificates.

“There’s this vocationalization of academia where the things that ground you as an individual are diminished,” said Lily Ann Villaraza, chair of Philippine Studies.

Villaraza defines ethnic studies as resistance, and believes it helps people understand themselves and their communities in a deeper and more meaningful way.

One of the issues, she points to, is the decline of programs that empower students to see themselves as leaders and as part of a larger solution.

“The fundamental question we must ask ourselves is what is a community college, and what are the other ways the institution can better support its departments,” she said.

From one generation to the next

Alvarado stood before a crowd at REVision CCSF: Our Struggle Continues, a student-run event held on April 18 that celebrated the legacy of SF State’s historic strike.

“What it took for our people to come here, to get by, to live on what it was that they made – one could never pay that back. But by moving forward and making a stand for yourself, to be represented and respected for who you are, that’s a payback. That’s a huge payback,” Alvarado said.

The former TWLF spokesman urged the room of over 100 attendees to band together and talk about their experiences. “Find those things that you share with one another, come together in an open dialogue, and begin to look at ways in which you can address your needs together,” he said.

As the musical performances and speeches of the night neared to an end, Tascoe extended one last message to the next generation of hope and change.

“Your job as leaders is to lead equitably. Claim your heritage, claim your history so that you can be thoroughly enriched in knowing who you are,” she said.