Art Instructors and Students Hone the Art of Perseverance

By Skylar Wildfeuer

Seventeen months into the ubiquitously traumatic pandemic experience, determined instructors and engaged students find consolation in the interpersonal and communal practice of teaching, learning, and art.

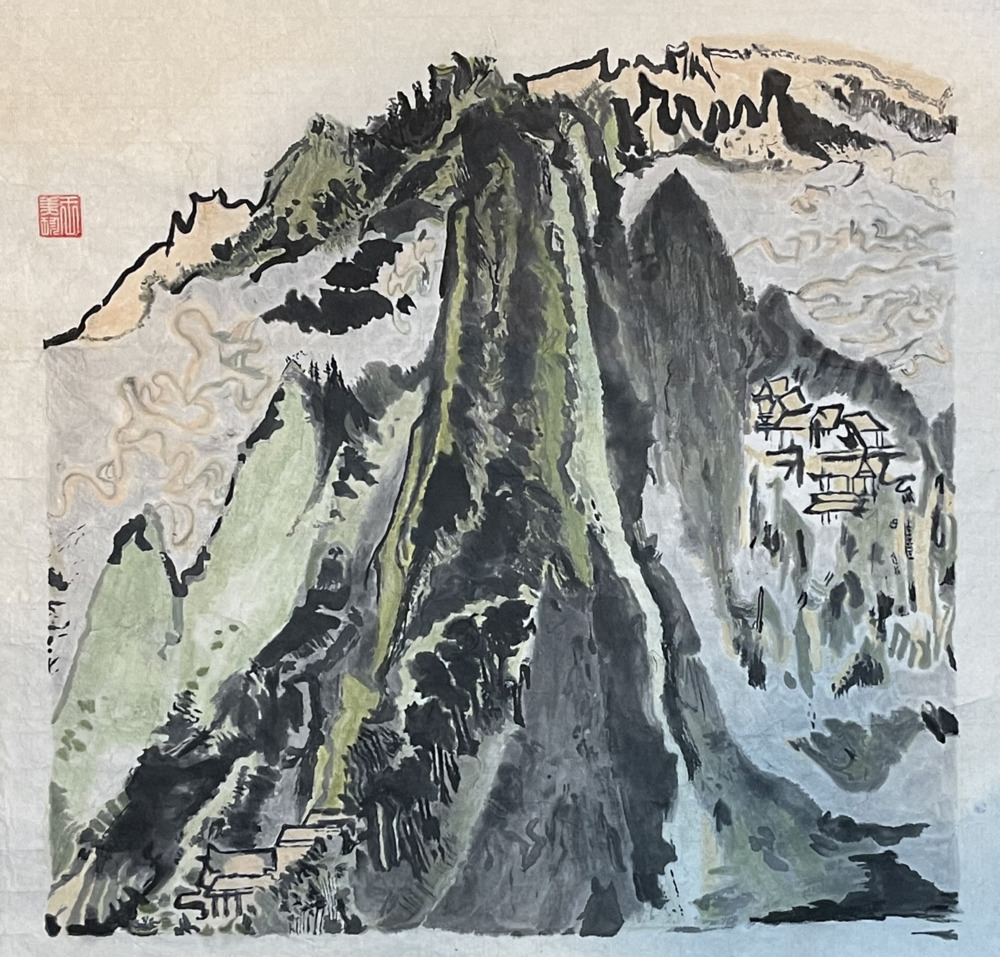

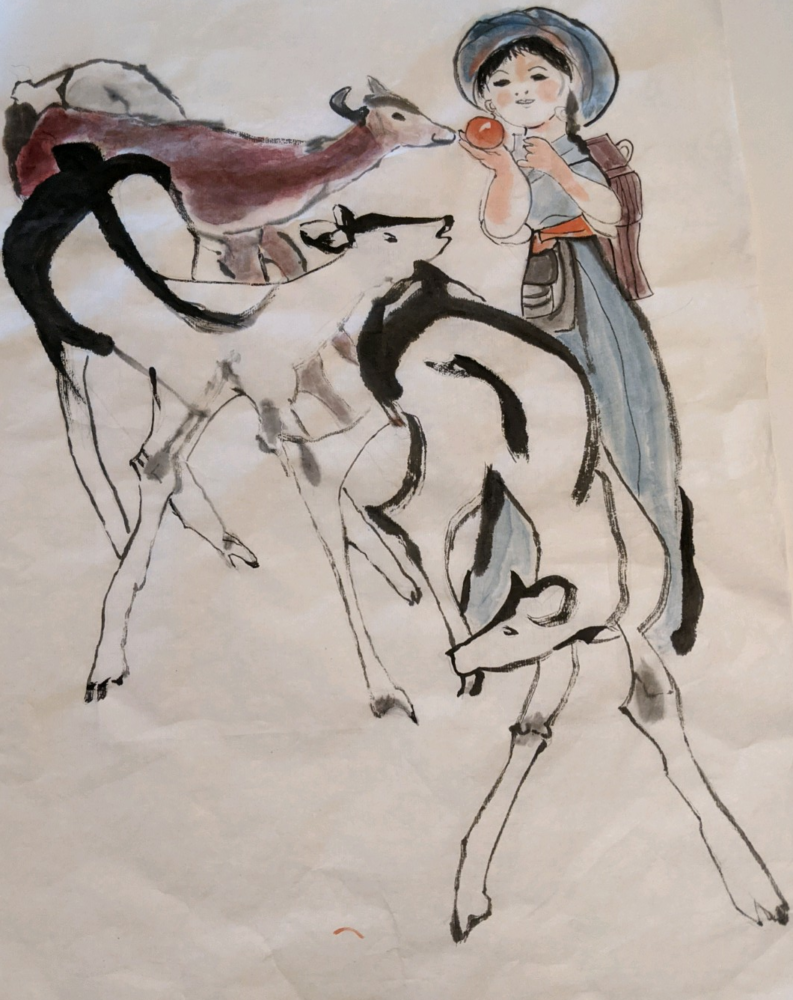

City College’s extensive art offerings include ceramics, metal work, printing, sculpture, and several types of painting, by instructors of caliber. Instructor Ming Ren has been teaching Chinese Brush Painting at City College for thirty two years and his work has been exhibited in museums all over the country and the world.

Instagram: @mxwsh

City College offers one of the only college courses in Chinese Brush Painting in the United States, and though students attending colleges all over the Bay Area sign up, the program has since its inception been not just for college students, but for everyone at every age, to enrich their lives while they work, or after they retire.

Ren spoke of the herculean adjustments undergone by the art department as they translated studio classes to online courses. Instructors have poured hours and effort into distanced demonstrations of their techniques. Now, everything must be written or planned, whereas, normally in a studio class, as Ren says, “We just talk with the students to share the knowledge in our minds directly.” There have been difficulties in purchasing and implementing the correct technology, and the current long-distance instruction technology used by the college is simply not set up for studio art instructors. Ren said, “I was struggling with a new program and also working very hard to make sure our education will be able to carry on.”

It has also always been a communal space. Ren said he has always facilitated a warm atmosphere in his classes, and is able to extend that to even more people while not limited to the physical confines of an in-person classroom. Despite the distance, Ren believes in the studio class as cultural engagement as much as ever.

He encourages students to compete only with themselves and celebrate their progress over the course of a semester. He is proud of his painting class as a meeting point for different cultures in a diverse region. He is very proud of the work that his students were able to produce. He said that the time stuck at home and the necessity of home studios actually facilitated significant progress.

Ren’s student Jeannie Wong characterized her pandemic experience as restrictive, that she was “Not free to go anywhere without second thoughts about being safe.” Another of Ren’s students, May Lee, articulated pandemic life as being, “Isolating, stressful, boring, terrifying.” Those four words resonated heavily with me.

The “bizarre world of the pandemic” as Lee put it has had a wild variety of impact on different people but has inspired many of us to be vigilant about safety and focused on extreme practicality. Vigilance fatigue leaves us disoriented and exhausted.

“Attending [Instructor Ren’s] class allowed me to meet with my friends,” Lee said, “attending class was normalizing.” The class seems to have provided Lee both social and emotional stimulation, “Practicing calligraphy calmed me down almost like meditation; mistakes didn’t matter and were sometimes funny.” I am so glad to be able to share Lee and Wong’s paintings from Ren’s class with you. I’ve so enjoyed sitting with these beautiful works over the past few days.

Fellow student Wong said of her experience, “Focusing on Chinese painting has helped me to preserve my sanity because it requires focus, concentration and consistency,” adding that when she produces a god work she is “thrilled,” and, “when it’s not good, I’m determined to work at it.”

I am not an artist or art student, but I am an audience and consumer of art. I was able to return to the SFMoMA post-vaccination this summer (the museum itself does not regulate). I viewed an exhibition there titled “Close to Home: Creativity in Crisis” containing bodies of work from seven bay area artists produced in response to, and in the throes of, the upheaval of 2020. I was most impacted by the titles of florals by Tucker Nichols, a painter who sends his florals in the mail to people who were sick on behalf of their loved ones, a project entitled Flowers For Sick People.

In an interview with the museum, Nichols said that, “Increasingly, the requests I’m getting are … related to the virus and people who are suffering from the virus, so it’s really this portrait of what people are going through and how cut off they feel from the people who they’re trying to take care of.”

Of course, the scale is changing. Nichols realized he could not send flowers to everyone who deserves them. “So,” he added, “I started posting images of flowers … as sort of tributes to segments of the population at large… and then also ones that were kind of about everyone’s experience of being inside.” He says that these flowers are an attempt to connect about a common experience in isolation.

The titles of Nichols’ works were comforting like missives addressed exclusively to me. I first saw “Flowers for Anyone Who Has Mastered the Proper Order of Mask, Glasses, Headphones, Hat” which paralleled my personal pandemic experience, as did the next, “Flowers for the Radius of A Sneeze.”

“Flowers for George Floyd” brought memories of shock and rage that I had not yet connected specifically with the pandemic itself. “Flowers for Those Who Didn’t Make It to the Hospital” and “Flowers for the Inconsolable” shoved me back into my grief. “Flowers for the Realization that Generally Speaking Humans Like to Be Around Other Humans” is an obvious observation, but I have missed humans this past year, and it was cathartic to see my loneliness expressed by another.

San Francisco State University student and artist Max Hollinger experienced that loneliness as well. Their first description of their own pandemic experience was as a service industry employee in San Francisco. “As a worker fundamentally you are being used, [but] when it came to the pandemic … the stakes were my life, to keep a business afloat. That’s complicated: a lot of livelihoods were linked to that business. The only choice I could make was to stop working, and not everyone can do that.” This pressure and perilousness has been profound for most of us. Hollinger mentioned “Being totally out of my depth.” Vigilance fatigue compounds with sheer bewilderment at extreme aberrance.

They said they felt utterly unprepared. The artist explained, “That’s really the emotion behind the void behind the hand. And then, the composition: I’m underneath and supporting, and the cocktails look weird and ominous in that space,” and added, “When I made this I was really angry and scared and I felt vulnerable. And I love this painting. I stand by it.”

While the pandemic itself has been isolating for Hollinger, having quit their job and lacking in-person classes, art making is a way to connect. “Making art during a time period defined by an event is working collectively.” Hollinger said they felt connected to everyone, and even more motivated to create, “Because the pandemic felt like the end of days, art making felt both more futile and more important than ever. I felt like I had a responsibility as someone who makes art to express and archive my headspace at the time.” Asked what it would mean to know that a work they had made represented another’s experience, they said, “I’d feel emboldened,” and that their sense of purpose in their work would be renewed.

Nichols’ work and the rest of “Close to Home: Creativity In Crisis” will be on exhibit at SFMoMA until Sept. 5. Instructor Ming Ren continues to offer a world class education in Chinese Brush Painting in four levels from beginner to advanced at City College. Instructors will continue to cultivate the internal development and communal life of the people of the Bay Area for as long as the state provides funding. Art students will find community and learn to create beauty. Artists will continue to express for us what we knew but could not say.