Ground-breaking documentary about LA riots invites conversation

By Adina J. Pernell

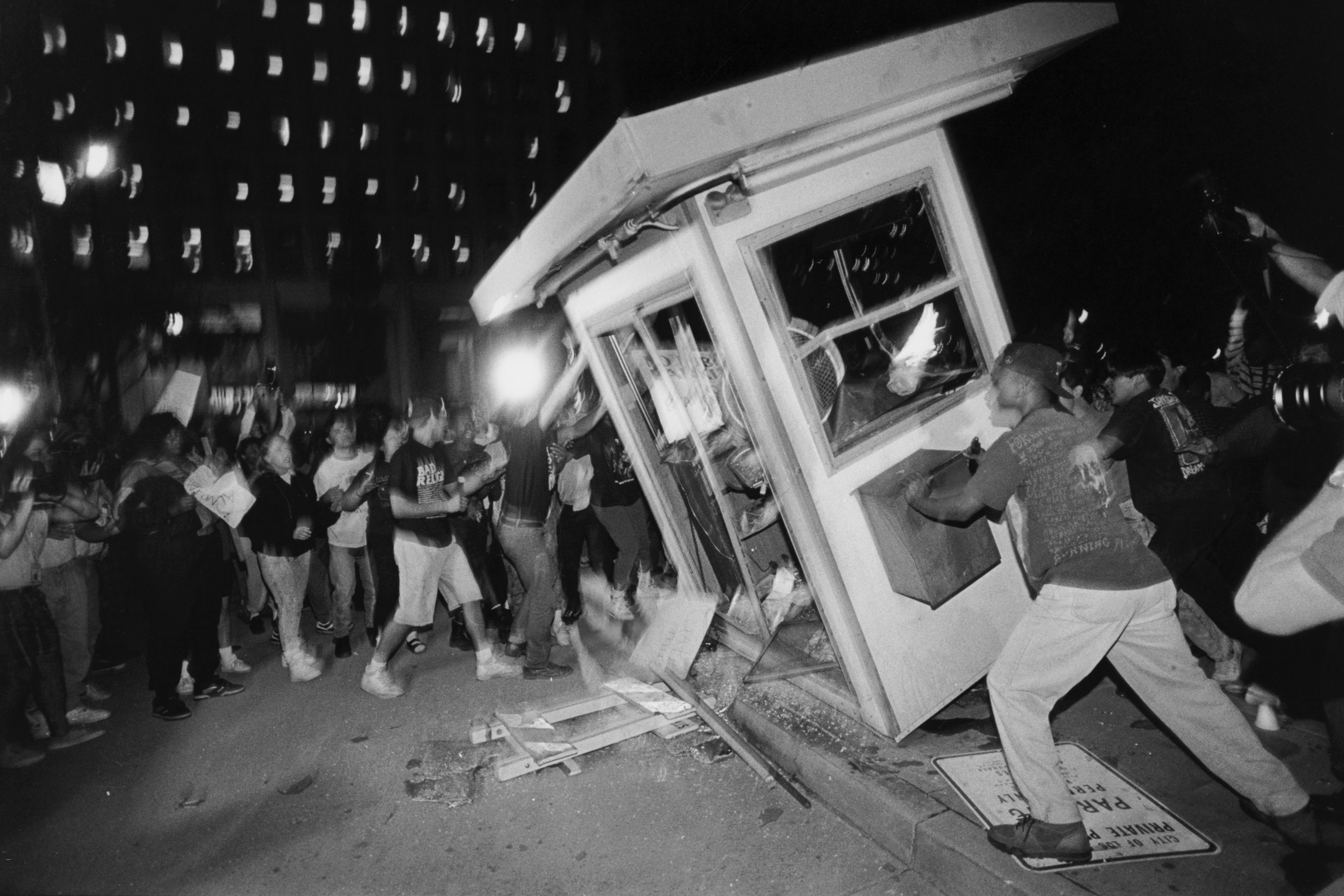

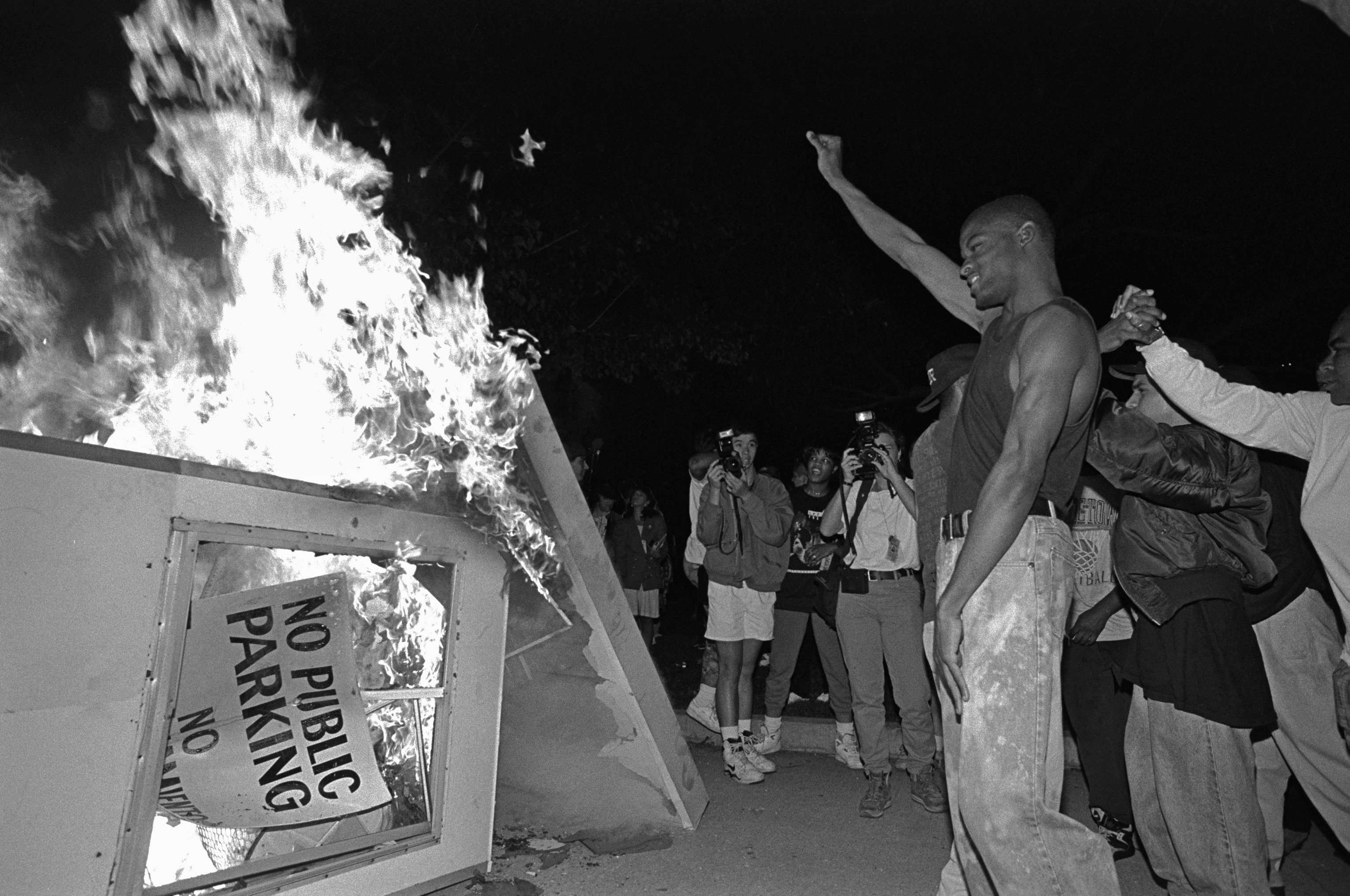

A quarter of a century has passed since the events that transpired after a not guilty verdict was delivered for the officers who savagely beat Rodney King on March 3, 1991, turned LA’s city streets into a swarm of looters, rioters and raging fires.

Long before the world entered the digital age, George Holliday, in what was arguably one of history’s first broadly televised incidents of citizen journalism, captured the heinous act on his camcorder from the vantage point of his apartment balcony. Holliday later released the tape to a Los Angeles news station and the rest was history.

The now culturally iconic footage of King’s beating, marked an early step toward a world of visual accountability and served as a picture of the racial state that America couldn’t look away from.

It’s hard not to compare Holliday’s actions to those of other modern day, citizen journalists like Saint Louis Alderman, Antonio French. French gave blow by blow coverage of the events of the protests in Ferguson, after the shooting of Michael Brown.

Oscar-winning, filmmakers T.J. Martin and Daniel Lindsay teamed up with Award and Emmy winning producers Jonathan and Simon Chinn and National Geographic to create a gripping cinematic narrative about the aftermath of one of the 20th century’s most racially telling occurrences of civil unrest in America.

The ground-breaking documentary, entitled “LA92” was told using mainly archival footage to chronicle not only the events that led up to the outbreak of violence, but also using newsreels of the infamous Watts race riots of 1965.

“LA92’” is Martin and Lindsay’s second documentary of note since their film “Undefeated”, snagged the Oscar for the Best Documentary Feature in 2012. This was quite a feat, considering that they never went to film school and have relatively few films under their belt to date.

After a special Screening at The Landmark Embarcadero Cinema in San Francisco on November 8, 2017, T.J. Martin, the other half of the directing duo, sat down with the audience and with Marc Philpart, Senior Director at PolicyLink.

PolicyLink, a national research and action institute for racial equality, to ask why Martin and Lindsay “embarked upon the journey for [the]film?”

Martin said that he was approached by Jonathan and Simon Chinn after they had pitched the idea for the film. “They had known the 25th anniversary that was coming up regarding the civil unrest in 92’” said Martin. The Chinn’s had shown Martin and Lindsay a teaser of film archives that made them decide to take on the project.

He remembered one snippet in the teaser that particularly affected him was of an African American man whose store had been looted. “[He was wielding a hammer at the beginning of the sequence and he’s saying ‘I come from the ghetto too. Why steal from me? You call this Black power!’”

In “92’ I was 12 years old,” revealed Martin, “so, watching the material, I think I was surprised by the amount of raw emotion that was captured on camera.” Later in the discussion, He related to the audience that background was bi-racial. “My mom is Black and my dad is White so when this project came to me, I did remember being in Seattle and seeing [the] footage, and the media telling me that these are race riots.”

The decision to keep an archive-based format in the film was a conscious one on the filmmaker’s part.“We try to tell the story [in] archive only [format], so there’s not a filter between you and the material, for the narrative to feel like it’s unfolding in front of the camera, and you are there experiencing it in real-time,” said Martin.

Martin and Lindsay wanted to create a 360-degree experience for the viewer as well as one that would help the audience empathize with several different viewpoints.

“We consistently shift [points of views] so that you feel like you’re getting not just the experience of the entire city, but also what happened according to local law enforcement, local government, the point of view of Korean merchants, or the point of view of community members in South LA.”

“It operates in our minds like it’s five movements,” said Martin of him and Lindsay’s vision. “And the intent is that [as] you go through [the] experience,” Martin continued, “[you] explore the different themes, the cyclical nature of these things, the parallels of 65’ and 92’ and what’s happening now.”

This structure of the film played a large part in the music which was symphonic in nature that drove its climactic moments. Martin and Lindsey didn’t want to do what had already been done musically for similar documentaries. “It’s always, you go to South LA and all of a sudden cue up hip hop. And I just had no interest in doing that – and this is coming from a hip hop fan.” For “LA92” the directors used award-winning composers Danny Bensi and Saunder Jurriaans. “They composed the entire thing within a matter of two months,” Martin said. “It was pretty incredible!

After one of the audience members and Philpart inquired why the film didn’t focus on current examples of police brutality that have been captured on camera in cases like Michael Brown, Eric Garner, and Philando Castile, he conceded that he and Lindsay had originally considered incorporating contemporary footage.

In the end they decided that “It was too obvious. In a practical sense. We didn’t’ want to dumb down the audience,” said Martin. “And the audience from our experience, even just doing test screenings, was already there emotionally. There was no reason for us to beat it over your head.”

Martin and Lindsay also decided not to focus on the international and national riots that were occurring outside of LA because they didn’t want to blur the film’s clarity. “The intention for us was always, can we make a film that was distinctly about LA, but is really holding up a mirror to America?” Martin said.

Philpart said the documentary “just seem[ed] like an immense research project,” and asked about “the number of hours that went into creating” the film.

Martin said that “pre-production and post-[production] got squeezed into nine months, “and the “200 [to] 300 hours of footage” they originally compiled, quickly expanded to “about 2000 hours of footage and [that he] was still incorporating and changing scenes up to the last two weeks before we (him and Lindsay) had to deliver the film,

A staggering amount of footage was gathered from both aired and unaired broadcast footage, radio, and citizen journalism.

One of the audience members was a commissioner for San Francisco Commission on the Status of Women, Julie D. Soo, who sits on several San Francisco Boards, including the California Democratic Party Executive Board as a co-chair of the Platform Committee.

Soo was pleased that the film showed the way that Korean Americans were impacted by the riots. “As an Asian American, I feel that sometimes Asian Americans are left out in the dialogue.” She went on to comment on the state of race relations in America in general, and said that “things seemed quiet for a while, but everything was simmering underground, and now it’s just explosive.”

Martin believed that incidents of police brutality have “always existed” and felt that as a nation “we’re just more privy to it, because we have our devices and we can access it easier.” The film’s intention has essentially been “to further explore the conversation as it relates to race and class in this country,” and to allow the “audience to experience [the film] in such a visceral way, that you come out having empathetic dialogue”.

For Martin and Lindsay, being a part of something that was timeless and had a real impact was very important. They wanted the film to make a real statement.

“Hopefully, like any great piece of work or art, we were exploring something deeper,” Martin said.

Film trailer: http://channel.nationalgeographic.com/la-92/videos/la-92-official-film-trailer/